I just listened to a brilliant podcast of Ezra Klein interviewing Zadie Smith, the best-selling author of White Teeth, On Beauty, and The Fraud. One comment from Zadie Smith really jumped out at me:

“People aren’t terrible, systems are.”

I might add that systems and culture are both problems that cause people to act terribly or suck them into terrible milieus.

In any event, I highly recommend this podcast for its insights about how we rethink where we place the blame for behaviors that may offend us—on the person or on the culture in which she/he/they was raised and/or on the systems that failed them.

I also just read Hope for Cynics – the Surprising Science of Human Goodness, by Jamil Zaki, a professor and Director of the Stanford Neuroscience Lab. Zaki trained at Columbia and Harvard, studying empathy, kindness, and how we can learn to connect better with each other. In this book, Zaki illustrates the differences between healthy skepticism and dark cynicism.

In one research study, Zaki asked thousands of subjects in many different countries a simple question: “What percentage of people, if they found a wallet on the street with lots of money AND with information about how to contact the rightful owner, do you think would reach out and return the wallet?” The average response was 5.

When Zaki actually conducted the experiment by leaving said wallet on a busy street, he found that 16 out of 20 reached out and returned the wallet – with the money still in it. Hmmm, it raises questions about our views of people we don’t know, doesn’t it?

The podcast, the book, and my own angst about the current state of the world led me to think more deeply about the dangers of demonization, particularly when we have a lack of empathy for and understanding of the people we are demonizing.

Demonizing groups of people means swiftly attributing malevolent intent to an individual and then extrapolating that judgment to the entire group. It’s a short step from demonization to generalization. In this post, I will explore the insidious nature of demonization, its far-reaching consequences, and the imperative to resist its allure if we aspire to cultivate a more harmonious and understanding world.

Demonization is an easy means of simplifying the complexities of human behavior by reducing individuals or groups to caricatures of pure evil. It often emerges from fear, ignorance, or a desire to justify prejudice. When we demonize others, we strip them of their humanity, transforming them into menacing threats that warrant our hostility and distrust. Think Springfield, Ohio, and the demonization of Haitian immigrants, fueled by a lie that they were eating neighbor’s cats and dogs. A recent poll found that over half of Republicans believed this dangerously false story. That poll, however, poses two challenges for me: 1) to observe the assumptions I make about the 50% who bought the lies, and 2) to resist demonizing the other 50% who didn’t.

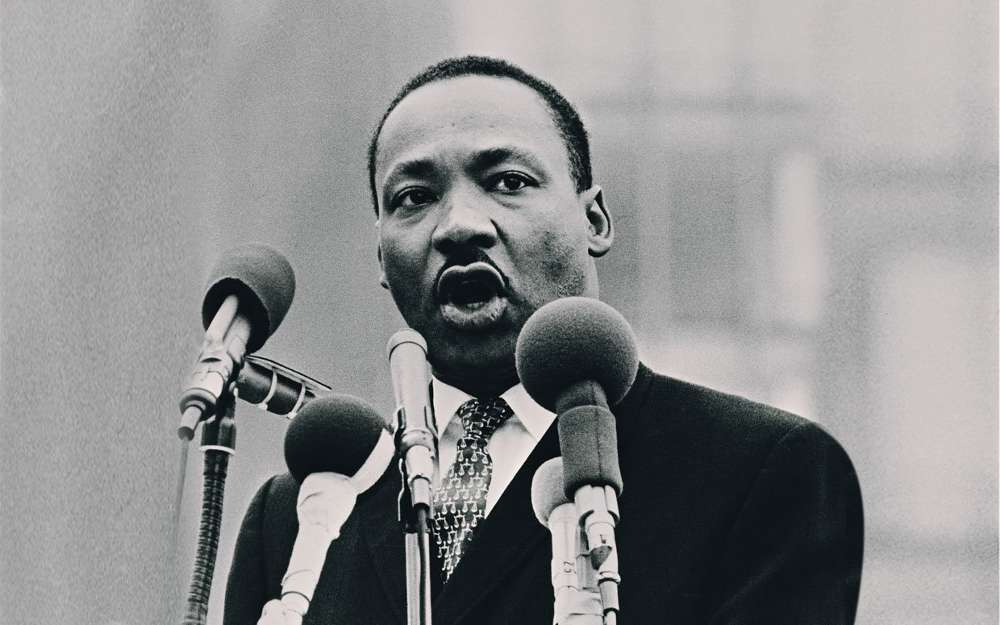

The consequences of demonization are profound and far-reaching. It fosters an “us versus them” mentality, erecting insurmountable barriers between individuals and communities. By painting entire groups with the broad brush of negativity, demonization fuels prejudice, discrimination, and even violence. It stifles empathy and understanding, replacing them with suspicion and animosity.

Demonization also perpetuates a cycle of conflict. When we perceive others as inherently evil, we are more likely to interpret their actions in the most unfavorable light. This can lead to self-fulfilling prophecies, where our own hostility provokes a defensive response from the demonized group, further reinforcing our negative perceptions.

The media often plays a significant role in the process of demonization. In their pursuit of sensationalism and ratings, news outlets may amplify stories that portray certain individuals or groups in a negative light. This can create a distorted public perception, where fear and prejudice flourish. The media is also driven by what drives the most traffic to their platforms. Sadly, according to Zaki, negative news garners far more attention than positive news.

The antidote to demonization lies in cultivating empathy, understanding, and a willingness to engage in open dialogue. It is essential to recognize the inherent complexity of human behavior and resist the temptation to reduce individuals or groups to simplistic stereotypes. By seeking to understand the perspectives and motivations of others, we can build bridges of communication and foster a more inclusive and welcoming society.

Critical thinking and media literacy are essential tools for combating demonization. It is crucial to question the information we consume, evaluate the sources, and be mindful of potential biases. By engaging in thoughtful analysis, we can resist the allure of sensationalism and develop a more nuanced understanding of the world around us.

In many traditions, demons are seen as subordinates of the Devil whose role is to tempt humans to sin, abandon their faith, or commit immoral acts. In the New Testament, the devil is portrayed as a unique entity determined, through any means, to rule the world. In Renaissance magic, demons are believed to be spiritual entities that can be controlled and conjured. In Japanese demonology, evil spirits can possess humans. In other cultures, demons have the power to corrupt and destroy. Clearly, there is a long history of demonization with many different beliefs, assumptions, and fears.

My first real introduction to demonization was introduced in Army basic training in which the Vietnamese people were dehumanized by referring to them as “G–Ks.” While I had heard sermons in church about the ever-lingering danger of the devil, and I had heard random racist comments in my small, white town, the language used in the military was jarring. I have been confronting those childhood tapes running through my head ever since.

Now, of course, demonization has been unleashed by world events, social media, political campaigns, and unhinged “leaders.” It’s easy to see the demonization of gender apartheid in Afghanistan and Iran. It’s impossible to miss the Russian (Putin) propaganda that Ukraine is run by Nazis. Chants of “From the River to the Sea” are not subtle in their implications for Jews in Israel. The evil initiated on October 7 by Hamas (Sinwar) is now being compounded by the disproportionate Israeli (Netanyahu) response in Gaza. In all of these horrors, hate has trumped compassion, and our humanity has been diminished.

In that global context, we are now spiraling into a dark place where the “other” is someone to be despised instead of understood. The assumptions, accusations, and assaults of two highly polarized parties toward each other have descended into violence. It’s an open question where this all ends.

So where do we begin? I think we begin by acknowledging the fact that no group is monolithic. While we tend to make assumptions about people in Red States and Blue States, for example, we know there is a wide range of perspectives and beliefs within each state. Yes, we can reasonably predict how 43 states will cast their electoral ballots, but we don’t know how many actually hold extreme views. We don’t know how much common ground we may have among the middle 60-80% of the population.

While I am definitely guilty of demonizing Trump and his MAGA extremists, I need to hold onto the possibility that there might be points of connection with a larger percent of that group than I tend to assume I have. I also need to understand more fully the reasons behind Trump’s appeal. Is it driven by anti-regulation fervor, elitist condescending attitudes, institutional distrust, fears of surging immigration, the price of groceries, gas, housing, and rent, the declining hope in the promise of the future, the protection of wealth and status, anti-abortion beliefs, gun rights, or religious ideology? Which of those drivers are predominant? Is there just one value driving the decision to support an egregiously unfit candidate. I don’t know. But I do know that my demonization tendencies are fueled when I assume ALL those decision-drivers are true for ALL supporters.

I believe there is evil in the world and that some people embody, embrace, and empower that evil. It’s too ubiquitous and obvious to ignore. I also acknowledge that I am too quick to demonize a whole group, when I don’t really know the cultures they have been exposed to and/or the systems they have been oppressed or exploited by.

I’m hoping I can do a better job of distinguishing who really merits the demon badge. Perhaps, deluded or disillusioned might be better terms for describing the followers of whatever group I may be demonizing. I hope we can all somehow avoid being consumed by the hate, fear, and disillusionment that poison our perspective. I’m hoping that all of us can do a better job of attributing fairly the causes of whatever behavior we see in the ”other” to the cultures that may have promoted the behavior and/or to the systems that may have reinforced the behavior instead of assigning blame immediately and fully to the evil inherent in the person. May it be so.

Also published on Medium.

A noble endeavor! Not sure I can get there but certainly agree with the premise…