“How does it feel to be on your own, without a home, like a complete unknown, like a rolling stone?”

“If the path before you is clear, you are probably on someone else’s.”

“Our common vision of a free and just society is our greatest source of cohesion at home and strength abroad, greater even than the bounty of our material blessings.”

Every day presents us with choices, the most essential of which is how we spend our time and what paths we choose. Do we focus on accumulating more material goods to satisfy our insatiable needs or do we invest our energy creating an environment in which all life can prosper? In short, do we dedicate our lives to acquiring commodities or to building communities?

Sometimes our lives feel like a rolling stone – ups and downs over hills, through valleys, with no sense of place or permanence. It’s always such a gift when we connect with loved ones and feel like we have returned to a home however we describe it. This holiday season I had the chance to connect with family and friends in NYC and experience once again what a beloved community feels like. Many years ago, I shared my experience finding a home in this vast universe in a book I wrote after returning from a month long retreat in China with a qigong master. Many other authors have also shared their own experiences in finding a home and experiencing the wonders of life and community.

In her new book, The Serviceberry, Robin Wall Kimmerer, describes what it looks like to build a gift economy and to experience the earth as our home. She illustrates how we have surrendered our values to a system that actively harms what we love and what we really need for a meaningful life. The kind of world she envisions is based on “reciprocity rather than accumulation, where wealth and security come from the quality of our relationships, not from the illusion of self sufficiency.” Kimmerer makes a case for sharing instead of hoarding, for interdependence instead of independence, for reciprocity instead of selfishness. She implores us to experience gratitude for the abundance of our gifts instead of grievance for whatever scarcity we perceive as missing in our lives. Hopefully, this book will get as much attention as her book Braiding Sweetgrass. The principles she proposes is critical for our survival as a planet and as a species – to say nothing of our souls.

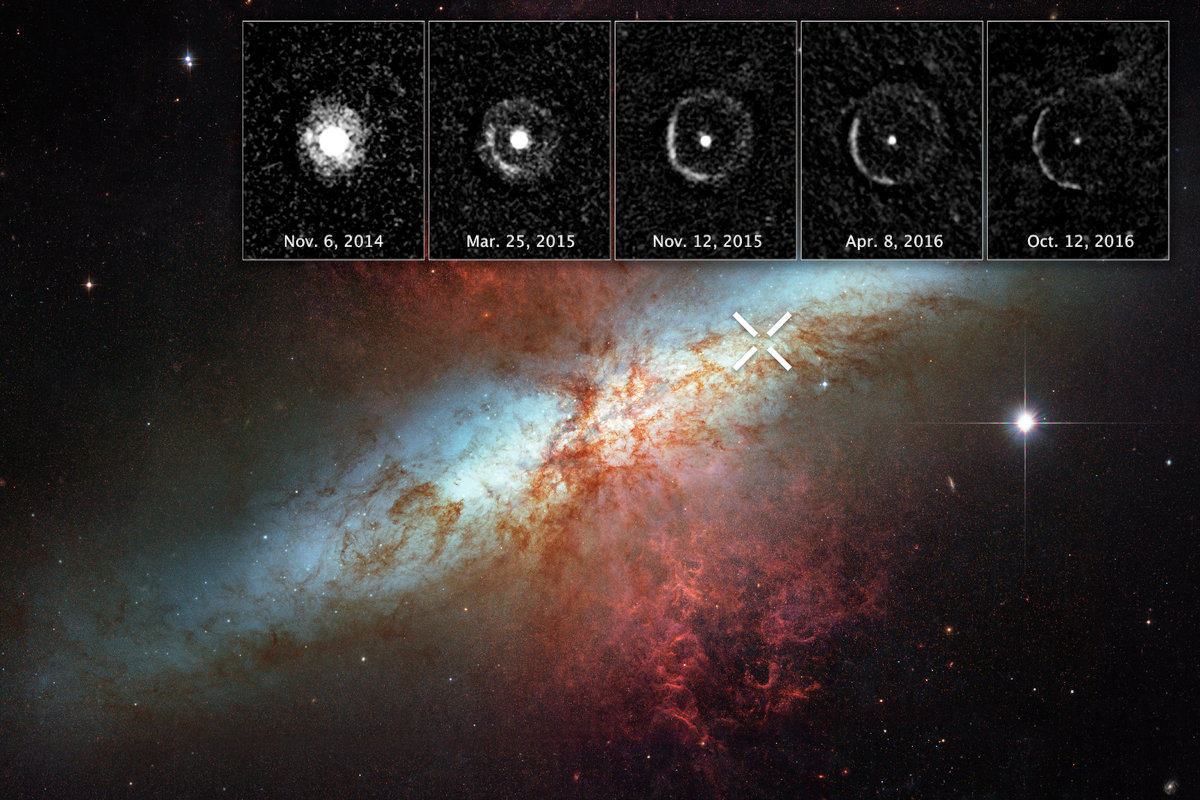

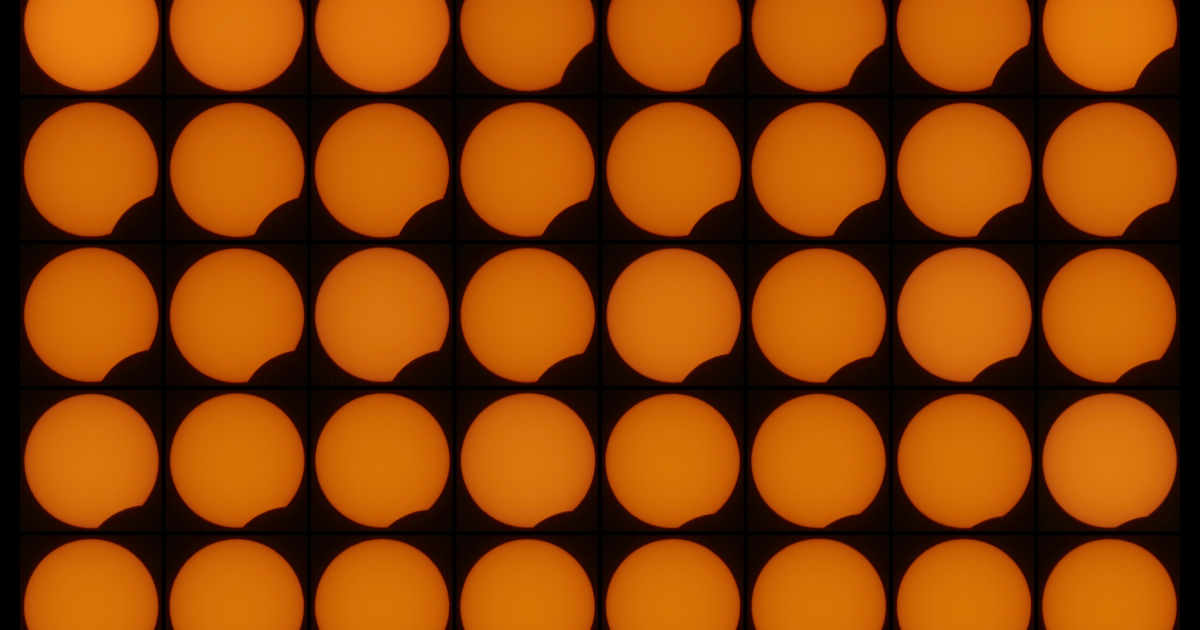

In a recent article in the New York Times, Dennis Overbye, the cosmic affairs correspondent, contrasts the world Kimmerer envisions with our current reality. He says, “Silicon Valley has led us to new realms of loneliness, squinting at tiny screens for fragile intimations of community.” He sets that reality in the context of on immense universe of trillions of galaxies and the steady rise and fall of stars. Over the span of his career as a “cosmic affairs” writer, he admits to being continually “ambushed by surprise and confusion.” He suggests we have reduced our lives to a tiny phone in our pocket from the boundless beauty of the galaxies – we constantly find ourselves looking down instead of looking up. I often feel the same way.

I thought the juxtaposition of these two images of possibility provided a great framing for this post. Kimmerer describes the small gifts of a garden right down to a single berry, while Overbye portrays the largest possibilities in an ever-expanding universe. Both share their gratitude for the full range of gifts that life offers – from the most granular grain to the most mysterious galactic glow. We are on our own in this great unknown. How are we going to roll?

I have the good fortune of living in a small, rural town in Northern Michigan where farming and gardening are dominant forms of life. I have also been lucky enough to have had the experience of living and working in New York, Boston, Washington DC, Toronto, Ho Chi Minh City and California. I have “danced” with the stars of finance, technology, health care, telecommunications, and consulting as well as dug for potatoes in the gardens of my rural community. I have had the good fortune of living in both worlds. At this point in my life, I can honestly say that I enjoy the dirt on my hands more than the dollars in my pocket. And, yes, I am privileged to be able to live the life I lead without wondering how to pay next month’s rent.

In world where many of us are feeling despair from the disasters of climate change, geo-political violence, nuclear proliferation, and domestic polarization, we find it difficult to find hope and trust that all will come out well in the end. So, in a feeble attempt to find a reasonable alternative, I will share an experience of what can happen at a local level.

At the risk of making it more of a climate refuge than it already is, let me give a shout out to the beautiful community in which I live. Traverse City has been featured in the Wall Street Journal as well as the New York Times in one of its “36 Hours In” series which highlighted local businesses, shops and eateries. It is also known as the “Cherry Capital of the World” with natural attractions like freshwater beaches, vineyards, and sand dunes. But, to me, what makes it special are all of the not-for-profit organizations that are looking out for people and the environment and are providing universal access to all of the pristine wonders of nature that the area offers. Here are some brief highlights of a few of them with whom I have had the privilege to work:

- The Grand Traverse Regional Land Conservancy preserves and protects natural and scenic farmlands and provides advance stewardship of those lands for future generations. In its 33 year history, the Conservancy has managed to provide public access to over 50,000 acres of nature, 150 miles of pristine shoreline, and over 125 miles of trails through forests, streams, and pastures. Their intent is to create a culture that inspires hope, innovation, and trust in the community. They openly explore the potential potholes on their path to purpose. People who engage with the Conservancy experience what happens when people work together to make things happen.

- TART, the Traverse Area RecreationTrails, provides a trail network that enriches people and communities. Its purpose is to promote active lifestyles and build connections. One of its many projects is the Nakwema trailway which connects multiple communities over twenty-five protected natural areas to create a 415 mile trail network in northern Lower Michigan.

- The Grand Traverse Regional Community Foundation supports a variety of nonprofit organization through meaningful grants and builds endowments that make lasting impacts for generations to come. Since its founding in 1992, the foundation has received more than $126 million in gifts and awarded over $73 million in grants and scholarships. This organization is a perfect example of how a giving culture can be created in a community of abundance.

- Rotary Charities of Traverse City, working in partnership with changemakers, provides funding, learning, and connections to address the region’s complex problems and create community assets for all. One great example of making this mission come to life is the Homeless Collective it brought together in a collaboration with the Community Foundation. This collective consists of over 20 key stakeholders working together to end homelessness in the Region. The stakeholders include the city and county managers, the chief of police, Munson Hospital, shelter directors, mental health providers, housing advocates, addiction treatment providers, neighborhood associations, and local faith organizations who mobilize to provide meals to unhoused people.

- Norte, an organization that empowers individuals of all ages and abilities to be physically active and socially connected through cycling. It creates safe and accessible active transportation options essential for building healthy, sustainable communities. Its youth programs are at the heart of what it does. By providing hands-on education and opportunities, Norte empowers children to develop lifelong habits that promote health, independence, and confidence. My grandkids participated in this program for several summers and loved it.

- FLOW, For the Love of Water, works to ensure the waters of the Great Lakes Basin are healthy, public and protected for all. The Great Lakes watershed contains 20% of all available freshwater on the planet. FLOW’s experts are committed to assuring the Great Lakes remain healthy in the face of current threats and work together with other community partners to preserve the water and chart a better course for generations to come.

These examples all illustrate what is possible when people work together to protect the gifts we have been given, to provide gifts to future generations, and to share the abundance in our lives and on our earth. The question is, do we want to settle for a “fragile intimation” of community or do we want to look up, speak out, and step into our respective communities with renewed hope and trust that we can make a difference. After all, what’s the alternative?

Creating collaborative communities is easier said than done. There is often a high level of cultural resistance to transformational change. During my recent holiday visit to New York City, my family visited a Jewish tenement museum displaying how Jewish immigrants were oppressed and exploited in the late 1800’s. We walked through a tenement building that housed many families during that period. The 350 square foot apartments consisted of three rooms (bedroom, kitchen, and living room) and often housed families of 10 or more people. This same space also served as a mini-manufacturing facility for the garment industry. Families spent practically all the money they earned (about $1 per day) on food and rent. When big Ag producers raised prices on meat, many families could barely survive. When the people in the tenement buildings decided to protest rising costs, they faced angry reactions from the capitalists in Chicago who were trying to increase their profits. The immigrants finally resorted to throwing rocks through windows and forming picket lines around all businesses who continued to sell meat at inflated prices. It took a fully engaged and committed community to push back against capitalist exploitation, but they ultimately got relief.

The experience in the museum triggered two questions for me:

- How far do we have to go to make a point and/or achieve our objectives?

- What narratives do oppressors create to justify exploitation and profit maximization?

Regarding question 1, the tenement community had to resort to mass protest and rock throwing to achieve any release. In the 1960’s, university students needed to occupy buildings and mobilize mass protests to end the Vietnam war. Malcolm X broke with Martin Luther King because of King’s insistence on non-violence. Now, individuals and organizations are targeting executives in the health care and fossil fuel industries because of price gauging and climate change. In every case, the battle lines were drawn between excessive commoditization and community collaboration. So far, commoditization has prevailed. Open questions remain on how far do we have to go and at what point do protests cross the line.

Regarding question 2, Jewish, Italian, Irish, and Polish immigrants were all dehumanized and demonized by capitalists to justify their dominant positioning and profit taking. Clearly, early American history is replete with stories of Native American genocide and African American apartheid. In both cases, white men justified their violence and exploitation by denigrating the people who lived on the land and who provided all the labor to build plantations and fortunes. Now, we are seeing the demonization of immigrants from Latin America, the Middle East, Africa, and Asia to justify further exclusivity and privilege.

The relentless pursuit of wealth accumulation through commoditization has been a defining characteristic of human civilization for centuries. For those of you who are interested, here’s a quick summary of this battle from the 17th century to our current situation.

The 17th century was marked by the rise of mercantilism, an economic system that prioritized the accumulation of wealth through trade. European powers, such as Spain, Portugal, England, and France, established colonies in the Americas, Africa, and Asia, extracting vast quantities of resources such as gold, silver, sugar, tobacco, and spices. These commodities fueled wealth accumulation in Europe, but their extraction came at a high cost.

- Dominant Commodities: Gold, silver, sugar, tobacco, spices

- Impact on Immigrant Communities: Indigenous populations in the Americas were decimated by disease, forced labor, and displacement. The transatlantic slave trade forcibly transported millions of Africans to the Americas, tearing apart families and communities.

- Demonization: Indigenous peoples were often portrayed as savages, while Africans were dehumanized and stereotyped as inherently inferior, justifying their enslavement.

The 18th century witnessed the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, marked by technological advancements and the rise of factory production. This era saw the growth of capitalism, an economic system characterized by private ownership and the pursuit of profit. The demand for raw materials and new markets fueled further colonization and exploitation.

- Dominant Commodities: Coal, iron, cotton, textiles

- Impact on Immigrant Communities: The Industrial Revolution led to mass migration from rural areas to urban centers, creating overcrowded and unsanitary living conditions for many workers, including immigrants.

- Demonization: Immigrants were often blamed for low wages and social problems, leading to discrimination and prejudice.

The 19th century was the age of imperialism, with European powers vying for control of Africa and other parts of the world. The pursuit of resources such as diamonds, rubber, and other raw materials intensified, leading to further exploitation and conflict.

- Dominant Commodities: Diamonds, rubber, gold, ivory

- Impact on Immigrant Communities: Colonial policies often disrupted traditional social structures and led to the displacement of indigenous populations.

- Demonization: Racial ideologies were used to justify European domination, portraying colonized and enslaved peoples as inferior and in need of guidance.

The 20th century saw the rise of oil as a dominant commodity, fueling industrial growth and transportation. Globalization led to increased interconnectedness and the growth of multinational corporations, which often wielded significant economic and political power.

- Dominant Commodities: Oil, natural gas, minerals, consumer goods

- Impact on Immigrant Communities: Globalization led to increased migration and the growth of diasporas. Immigrant workers often faced exploitation and discrimination in their new homelands.

- Demonization: Anti-immigrant sentiment often resurfaced during times of economic hardship, with immigrants scapegoated for job losses and social problems.

In short, the relentless pursuit of profits through commoditization has had a profound and often destructive impact on communities throughout history. The extraction of resources has led to environmental degradation, displacement, and conflict. The pursuit of profit has often come at the expense of human rights and social justice.

The commodification of resources and labor can erode community bonds, exacerbate inequality, and contribute to environmental degradation. It is crucial to recognize the social and environmental costs of our economic system and to strive for a more just and sustainable future. There has been a consistent pattern over time how specific commodities have fueled economic systems that exploit both human and natural resources. Immigrants typically bear the brunt of exploitation through low wages, poor working conditions, and social demonization. This demonization has led to an erosion of community as well as environmental damage.

As we near the end of the first quarter of the 21st century, the commodities have changed, but the behavior perseveres. Now, the primary commodities are personal data, rare earth materials essential for electronics, and complex financial products that lead to speculation and create economic instability, benefiting the wealthy while leaving the less fortunate more vulnerable to financial crises. The shifts to technology and AI have further exacerbated these problems leading to job displacement and discrimination.

It is more essential than ever for communities to come together to promote ethical consumption, informed choices, and enlightened environmental practices. More than ever, governments need to regulate industries to ensure fair wages, safe working conditions, and environmental protection – including increased transparency in supply chains. At some point, we will need to see ourselves as one big international community collaborating on issues like climate change, and collectively resisting exploitation. And yes, progressive taxation will be required to ensure a social safety net and to mitigate the inequality created by the relentless pursuit of wealth.

I hope we will start listening more to artists like Bob Dylan who make us ask what it feels like to be on our own, without a home, in the great unknown. I’m also hoping we will heed the advise of psychologists like Jung who ask us to create our own path instead of blindly following someone else’s. I’m hoping that, as Jimmy Carter implored us, that we can create a free and just community as our greatest source of cohesion – greater even than the bounty of our material blessings. Indeed, I’m hoping we will finally shift our focus from acquiring commodities to building inclusive communities. May it be so.

Also published on Medium.

Wow! Well done lad!

Even better second time through! Thank you!

[…] family, daily practices (reading, writing, meditation, music, health) and my local projects with several not-for-profits. Again, the people I care about and work with are in the best position to assess how well I am […]