“My theory is this: Rather than having commentaries from the cheap seats, get involved and see what you can do. What can you do around your own community, within your own family, to try to improve race relations in our country? I think this is a responsibility that we all have as citizens.” —Valerie Jarrett

I guess I could be accused of commenting from the cheap seats, but race is an issue that affects all of us and we all need to contribute to the solution. Yes, I’m white, I grew up in a homogeneous, white community, and I have no idea what it feels like to grow up black in America; AND, as a father of a multi-racial family, I’m personally invested in improving relationships among all racial and ethnic groups. So at the risk of being another white, liberal male patronizing from a safe soapbox, I will share my perspective.

I’m writing because I want to own my white privilege, admit my unconscious biases, and frame the issue of race relations with a constructive analysis of where we are and where we need to go as a society.

To me, evolution is always about “moving up the scales.”

That movement requires us to be impartially objective, passionately aspirational, and relentlessly disciplined.

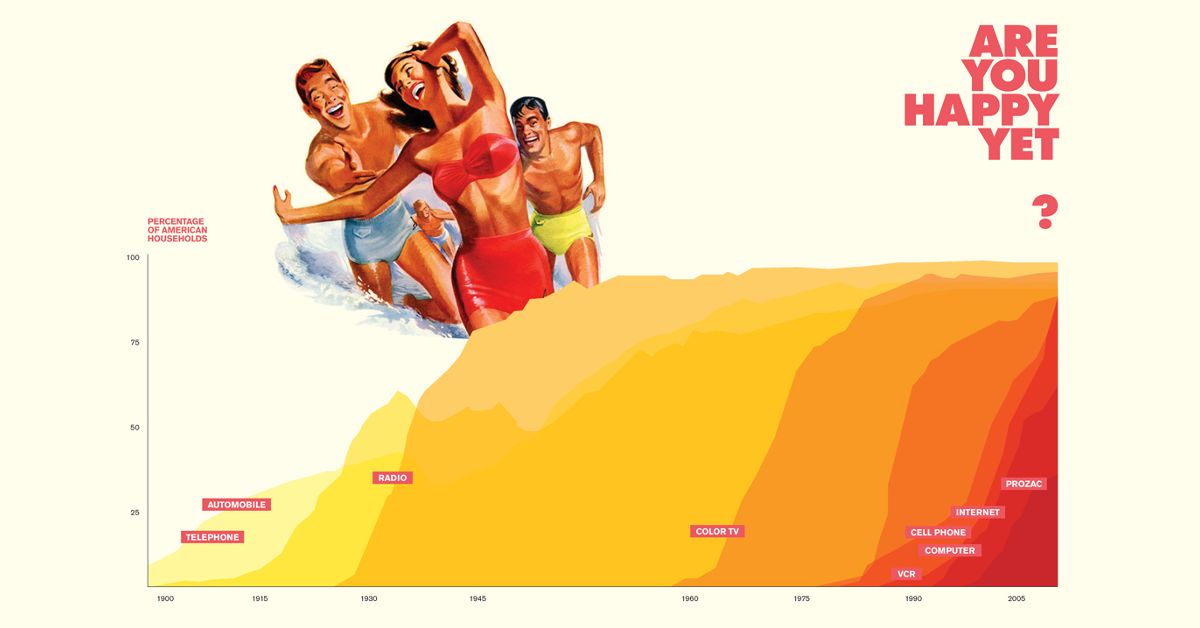

In previous posts, I have shared several scales that help us assess our current state and a desired future state. Here’s my scale for race relations:

- 5: Space relations—creating safe places where all can shine

- 4: Grace relations—genuinely welcoming differences

- 3: Race relations—appreciating and accepting differences

- 2: Face relations—reacting negatively to appearance

- 1: Mace relations—aggressively abusing fellow citizens

If we were to map the American population on this scale, I’m not sure what the frequency distribution would look like. I do know that it would not be pretty.

Before you make your own assessment, let me describe what relationships look like at each level.

I will start at the bottom and move up the scale.

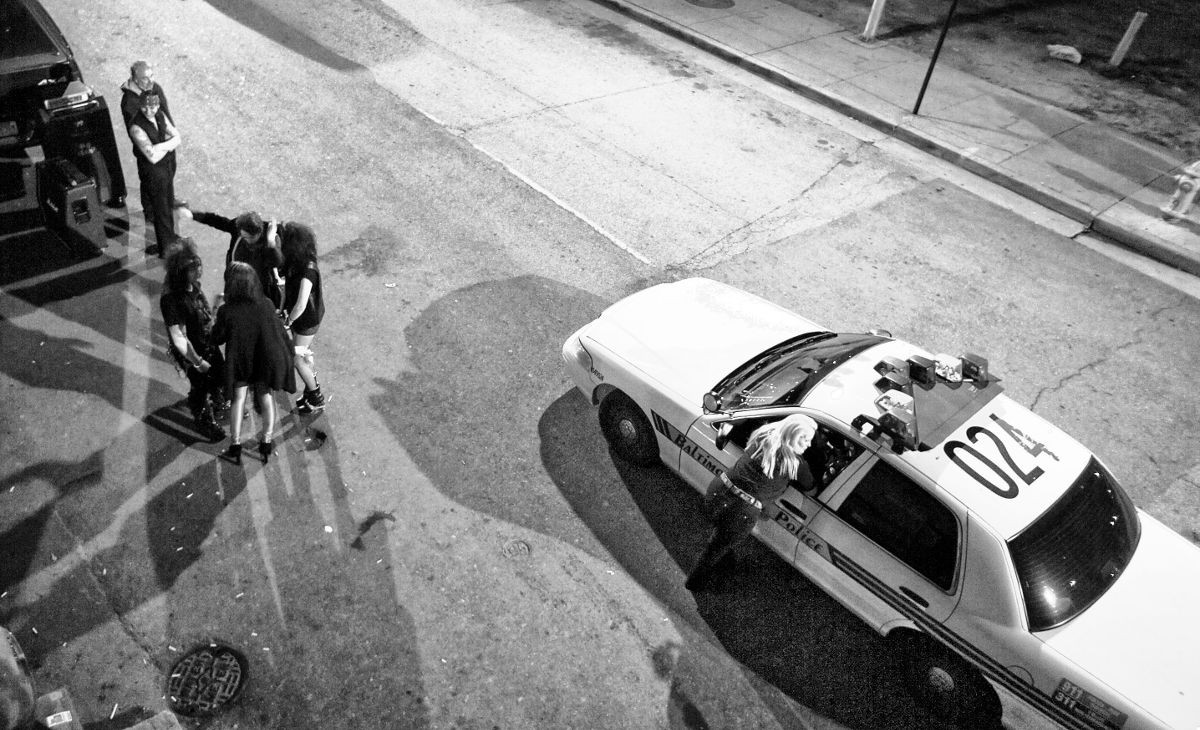

1. Mace relations: This means we treat each other with hostility and violence. I recently read Angie Thomas’s excellent book, The Hate U Give. In this brutally honest novel, a 16-year-old black girl, Starr, is desperately trying to navigate two worlds—the poor, gang-infested neighborhood where she lives; and the elitist, suburban prep school which she attends. Her world is shattered when she witnesses the fatal shooting of her childhood best friend by a trigger-happy, white police officer. Her friend was unarmed and was not threatening the officer in any way. The cop shot him three times in the back for the crime of moving when black. Immediately after the shooting, the news coverage describes him as a drug-dealing thug. Protesters take to the streets. Some cops try to intimidate the girl and her family. Sound familiar?

Having worked with and trained cops for eight years, I understand the fear and anxiety that police officers experience when they are called into hostile, tense, and threatening situations. Cops deal with human tragedy on a daily basis. The cumulative experience surely must wear them down and make them jaded. Until you’ve walked a mile in their shoes, it’s important not to generalize individual behavior to the whole police population nor to jump to conclusions on what constitutes an appropriate use of force. The ugly truth, however, is that our history is filled with stories of unjustified violence against African Americans in particular, but on other minorities as well.

Starr may be subjectively partial in her analysis, but she also makes the profound point that white Americans have always “mattered more.”

In another powerful book, White Rage, Carol Anderson exposes the unspoken truth of our racial divide.

She documents the deconstruction of Reconstruction and recounts the brutal violence blacks experienced at the hands of Southern whites who refused to accept the outcome of the Civil War. She then traces that animus all the way to our current situation and our current President. Anderson helps us to understand whiteness in the light of our national history—the use of state power to engineer preferential treatment for whites while imposing cumulative disadvantage on blacks.

Essentially, white hate and anger are related to any advancement of blacks that diminishes white privilege and power.

Anderson, a professor of African-American studies at Emory University, suggests that we are witnessing white backlash at a moment of black progress—triggered and symbolized by President Obama.

I believe white people need to get educated about our whiteness AND the experience of being black—even if vicariously through reading. My voice on race relations is weak in comparison to the historical experience of blacks in America, but I believe every white person in America needs to read White Rage, The Hate U Give, Just Mercy and any book by Ta-Nehisi Coates, e.g. Between the World and Me, The Beautiful Struggle, or We Were Eight Years in Power.

Without a deeper comprehension of the history and experience of black Americans, it is impossible to engage in meaningful conversations about race.

Facts related to race relations have been often obfuscated and/or obliterated.

Here’s a summary of recent research:

- Racial minorities make up about 37% of the general population, but they make up 63% of unarmed people killed by police.

- Black people are much more likely to be arrested for drugs even though they are not more likely to use of sell them.

- Black inmates make up a disproportionate share of the prison population.

- When officers fire their stun guns, 56% of the victims are either black or Hispanic.

- Black boys are more likely to be held responsible for their actions than white boys—who are assumed to be essentially innocent.

- A person with a “black-sounding” name is assumed to be physically larger, more prone to aggression, and lower in status than a person with a “white-sounding” name.

- People with “white” names are 50% more likely to be called back for job interviews.

All of these facts substantiate the evidence that all of us are vulnerable to unconscious bias, if not outright racism.

I’m guilty of making snap conclusions that blacks and Hispanics are more likely to engage in bad driving behavior than whites. When anyone on the highway does something to cause me road rage, my first reaction is to assume it was a person of color. I am not claiming to be free of unconscious bias or cultural conditioning.

2. Face relations: This means we make judgments on appearance. Recent stories highlight the frequency of actions taken for the crime of being black, e.g. two black men being handcuffed and removed from Starbucks for asking to use the bathroom before ordering a cup of coffee, a Yale student being called in by neighbors for taking a nap in a student lounge, ad nauseum.

Being black means hearing door locks click shut when cars are stopped at a light, seeing taxi cabs take a look and drive right by, being shadowed by employees when shopping, and a hundred other ways of being demeaned by people’s assumptions.

These kinds of knives may not draw blood, but they cut deeply.

3. Race relations: This means we start seeing each other as equal partners in the human race. It means recognizing and appreciating differences, but acknowledging that we all come from a common source and are at One with all races on this planet. To me, this needs to be the starting point in our march to harmonious inclusion. The civil war was fought to end slavery—the most egregious example of inequality. And the fight still continues.

Until we own our unconscious biases, the war will go on in perpetuity.

4. Grace relations: This means we have the grace and wisdom to welcome differences and leverage them. It means seeing differences as gifts to be valued instead of annoyances to be tolerated. To me, showing grace requires acceptance, forgiveness, and compassion. There is a big difference between tolerating differences and truly welcoming them. Grace demands that we act patiently, positively, gently, and sensitively.

When we are over-identified with our race or tribe, it is difficult to demonstrate grace.

5. Space relations: This means we create the space for people with love in their hearts to grow and contribute. It means we have to create environments in which people can grow, bloom, and radiate. The history of race relations has been confinement and containment. We need to expand spaces for growth, not reduce them through unequal educational opportunities, housing options, and economic possibilities.

The primary condition for creating a healthy environment is love.

We need to let people know they are loved for who they are. It requires us to take a hard look at ourselves, to make ourselves vulnerable, and to embrace each other with kindness in our hearts.

I try to give my grand-kids loving hugs and affirmations every day. It makes me sad to think how many of us grew up without warm, squeezing hugs. I certainly didn’t get them as a child and my children probably didn’t get as many as they deserved. I believe all of us would be less prone to angry reactions if we had experienced deep and continuous love when we were growing up. A case could be made that we all suffer from PTSD at one level or another. Clearly, many of the children growing up in minority communities are not benefiting from the spaces that would nurture their growth in homes, schools, and communities.

For kids growing up in environments where they are not only different, but also assumed to be “less,” I can’t even imagine the pain they suffer.

As a society, if we are going to move up the scale from mace relations to grace and space relations, we need to look at ourselves and our society with impartial objectivity, to passionately pursue our aspirations, and to commit to relentless discipline.

Krista Tippett, in a recent podcast with John A. Powell, discussed the importance of belonging in race relationships.

Professor Powell teaches at UC Berkeley and is the Director of the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society which brings together researchers, scholars, and policymakers to identify and eliminate the barriers to a just society and to create transformative change toward a more equitable world.

In the podcast, Powell makes the points that race is deeply relational, that we are all connected, that we all are trying to save our souls, that we all need to feel like we belong, and that when people of all races come together we learn to love each other.

He urges us to work to create a beloved community in which people believe that love is more powerful than hate.

He suggests the goal for all of us is to develop a larger and different “we.”

It seems to me that John hits the nail on the head. He not only is passionate in his aspirations, he is also objective in his assessments of where we are and where we need to be. In addition, he has been relentlessly disciplined in pursuing his dreams. I highly urge you to listen to the podcast, to get out of the cheap seats, and to get involved.

I believe we need to view the challenges of race relations more from a vantage point of fear than of hate. Most of what we see in the media are manifestations of hate—police violence, angry confrontations, screaming protesters.

Perhaps we need to look behind the hate and see and hear the fear that is at the root of our divided state: fear of being left behind, fear for our children, fear of losing status and jobs, fear of being killed.

Fear is more relatable than hate. If we can get beyond the outward expressions of hate and understand the inner fears behind that hate, we will be more likely to show loving compassion than raging reaction.

In conclusion:

Let’s relate on race

And create a space

Where there is not a trace

Of hate in our heart

Let’s find the grace

To stop using mace

To quit judging on face

And to love as a start

Also published on Medium.

Well done Ricky! Thank you