How communities address homelessness issues provides a great example of what happens when you chase symptoms instead of change systems that are causing problems in the first place.

Finding solutions to help people experiencing homelessness presents the same kinds of challenges communities face in dealing with health, criminal justice, poverty, inflation, immigration, climate change, gun violence, etc. The choice always involves investing in ways to improve the systems creating the problems vs. dealing with symptom consequences of the broken systems. (For a more universal look at symptoms and systems, go to this post.) The challenges are to find and fund the resources required to improve the system.

In this post, I will zoom in on the challenges associated with the growing homelessness problem and then zoom out to all the systems change problems the US government needs to address. I will show how all the problems come down to resource allocation issues.

It’s fair to say that almost all people experiencing homelessness are sad symptoms of broken systems – whether the system most at fault is education, criminal justice, healthcare, economic, political or social.

In order to develop effective solutions and models to deal with the unique symptoms associated with homelessness, each community must address those systems not only to prevent symptoms from getting worse, but also to assess short term and long term needs, to connect people with the resources required to meet those needs, and to track progress so improvements can be made. Several communities have taken novel, humane, and tailored approaches to repair some of these inefficient and ineffective systems in their respective communities. All of these solutions require thoughtful resource allocation decisions.

Nearly a decade ago, two U.S. cities with large homeless populations tried to solve their problem by adopting a strategy that prioritized giving people housing and help over temporary shelter. Houston and San Diego took fundamentally different approaches to implementing that strategy. Houston revamped its entire system to get more people into housing quickly, and it cut homelessness by more than half. San Diego attempted a series of one-off projects but was unable to expand on the lessons learned and saw far fewer reductions in homelessness.

Despite those outcomes, the cities are again charting different paths in deciding how to use millions in taxpayer money that Congress approved to care for the homeless as part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES). Houston is focusing much of its unprecedented amount of aid on permanent housing and homeless prevention. San Diego, with its chronic shortage of affordable housing, is prioritizing temporary shelters. Deciding how to allocate resources to the various components of the system is always a major issue.

The Housing First approach to homelessness prioritizes giving people housing and additional support services. In the 1990s, it was a revolutionary idea because it didn’t require homeless people to fix their problems before getting permanent housing. Instead, its premise — since confirmed by years of research — was that people are better able to address their individual problems when basic needs, such as food and a place to live, are met. It puts a lot of responsibility on communities and on organizations to really understand what their clients need and want, and to center people in the processes for deciding how to help.

Housing First became the guiding principle for homeless programs led by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, which created financial incentives for communities that followed that approach. It was not embraced without criticism and controversy. Thus Congress included wording in the CARES Act that barred any of the $4 billion in pandemic homeless aid from being used “to require people experiencing homelessness to receive treatment or perform any other prerequisite activities as a condition for receiving shelter, housing, or other services.” Thus, even when resources are available, decision makers need to take into account the conditions associated with those resources.

As a result, too many people around the world are unhoused. Several communities, however, have found compassionate and effective ways to get them the housing and support they need to survive and thrive.

Medicine Hat, Canada, for example, located in Saskatchewan, Canada, has nearly 20% of the city’s residents living below the poverty line. And yet it has a functionally zero homeless population. Why? Housing First. People experiencing homelessness in Medicine Hat are first provided housing without any preconditions, then offered support to address other issues they may face. After providing the unhoused a home, the city works on secondary issues such as the provision of physical and mental healthcare or addiction recovery services. Helsinki, Finland, is another example of what happens when housing is unconditionally provided. As a result of its approach, practically no people go unhoused. Japan also has very few people experiencing homelessness. When resources are appropriately allocated, communities can be successful in addressing this issue.

Multiple studies show that when people experiencing homelessness are offered supportive housing, most take it and stay for the long term. Participants in housing first programs have far less interactions with law enforcement and a much lower rate of shelter stays. Other cities that have adopted similar approaches have seen tremendous success. For instance, Salt Lake City reduced its chronically homeless population by 91% in just ten years using the housing first approach. Cities in Colorado, Wisconsin, and New Mexico have followed this model as well.

Napa, California has created a one-stop shop for people experiencing homelessness. The Hope Center had been in a building owned by the Napa Methodist Church for over 20 years. The center is adjacent to an affluent neighborhood, and neighbors have had multiple community meetings to address problems caused by some Hope Center clients, such as drug abuse, littering and trespassing. Not surprisingly, while Napa sees itself as a caring and generous community, it has had to grapple with the fact that the center has created problems. Recently, the county, city and churches worked together to establish the South Napa Shelter which consolidates daytime and overnight services closer to the people experiencing homelessness but farther away from the downtown area. This solution, however, can create transportation and isolation challenges.

In Santa Clara, California, a five-year plan to end homelessness was organized around three main strategies: 1) Address the root causes of homelessness through system and policy change, 2) Expand housing programs to meet the need and 3) Improve the quality of life for unsheltered individuals and create healthy neighborhoods. Their plan targeted reducing the annual inflow of people becoming homeless, increasing the number of people housed through a supportive system, expanding the prevention system and early intervention services, reducing the number of people sleeping outside, addressing racial inequities, and tracking progress toward equitable policies for all.

What emerges from all these studies is that communities need to find both short term and long term solutions for people experiencing homelessness. Short-term solutions are usually some combination of shelter + emergency interventions services. Long-term solutions typically focus on housing first + support. Both solutions require governmental and law enforcement funding and coordination. Venn diagrams illustrating the overlapping circles and interdependent relationships among these solutions, show where there is overlap and complementarity. Thus, success depends on a combination of compromise and collaboration.

What’s important to recognize is that no single service provider can solve the homelessness crisis alone. Long-term success requires strong collaboration among service providers, local government, and the community. Ending homelessness means more than just providing shelter—it requires a comprehensive approach that includes both emergency shelter and a significant increase in supportive housing. For efforts to be truly effective, there needs to be a focus on securing funding and developing more affordable and permanent supportive housing alongside expanding shelter capacity and ensuring safety for all members of the community. Ultimately, the solution requires stakeholders to decide how much to allocate to supportive housing, services, shelter, and safety.

No matter what the Venn diagram looks like in a particular community, the solution to homeless and housing appears to consist of four processes captured by the acronym PACT: Preventing, Assessing, Connecting, and Tracking. It is always important to identify root causes for any problem and to identify ways for Preventing those causes from gaining strength. Assessing early warning signs enables all stakeholders to be aware as early as possible to a crisis and to intervene as quickly as possible with the right housing options and services before symptoms become unmanageable. Connecting people to the resources they need to find housing, receive treatment, and get required support may be the most critical component of homeless response systems. Finally, Tracking people experiencing homelessness as they go through the system helps to understand where people fall through the cracks and where they need additional support. Also, tracking enables leaders to measure results and form a business case for further funding.

All of the components and processes boil down to resource allocation issues. Unfunded words are not enough to achieve success. While the most successful communities invest heavily in supportive housing, others choose to allocate a disproportionate share of their resources to safety issues surrounding unhoused people in neighborhoods who don’t want them there. When a community over-indexes on safety, the human costs and casualties can be catastrophic.

Making the right resource allocation decisions is critical to the success of solving any systems issue. Health care is an obvious example. The pharmaceutical industry, a dominant player in the system, is primarily focused on treating symptoms instead of improving the systems that could be causing those symptoms – that’s where the money is. If the health care systems allocated more of its resources to preventing illness by promoting healthy lifestyle behaviors we would have far fewer symptoms to treat. A recent study showed that about 75% of Americans are overweight. It seems to me it would make good sense to promote diet and exercise in addition to selling drugs like Ozempic.

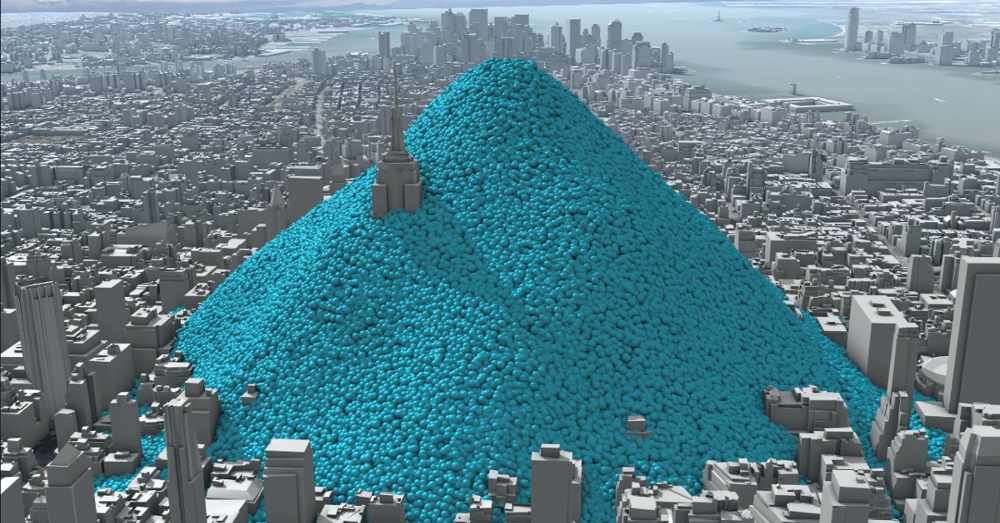

To zoom out on the larger context, let’s look at the U.S. budget. Currently, the government takes in about $5 trillion in revenues, but spends about $6.8 trillion. Five major expense categories account for about $1 trillion each: Social Security ($1.4T), Medicare ($1T), Medicaid ($.9T), Defense ($.9T), and interest ($.9T) on our $35 trillion debt. That means that any investments beyond those five line items require taking on additional debt. (Those five line items ($5.1T) exceed total revenues or $5T). It’s no wonder we have trouble finding the resources to fund systems change in education, health, criminal justice, infrastructure, immigration, environmental protection, and basic research.

As a result of the current election, finding the resources to fund these issues could be more difficult. Trump wants to cut taxes which means fewer revenues coming into government coffers. If he follows through on his promise to appoint Elon Musk as his “Efficiency Czar,” Musk intends to cut $2 Trillion of government spending. You can be sure that won’t come out of SpaceX contracts. Trump has also promised not to cut Medicare, Social Security, or Defense so the national debt (and thus interest on the debt) will continue to grow. Therefore, if Musk wants to cut $2 Trillion from the budget, it essentially means that all funding for EPA, Education, Criminal Justice, HUD, Medicaid etc. will have to be significantly reduced. To compound the problem, if Trump carries through with his tariff threats and mass deportation, inflation will no longer stay at 2.1%. In short, revenues will shrink, inflation will rise along with interest on the debt, and federal spending to solve system problems will be practically eliminated. All of these changes will put enormous pressure on state and local governments. Perhaps the people who voted for Trump should have been more careful about what they wished for.

I’m hoping that all the campaign bluster that got Trump elected won’t translate into the hard realities described above. His promises were essentially based on a combination of magic and miracles that only he could deliver. Even though his claims were unsubstantiated by research and rigorous analysis, they held enough appeal to enough voters to win.

I’m hoping (naively) that the draconian measures that will impact the most marginalized among us, who will be hurt the most by rising inflation and diminishing support for housing and healthcare, won’t come to fruition. Deporting 20 million immigrants is not only cruel but counterproductive. Imposing across the board tariffs on all imports is not only bad economic policy, but will also disproportionately impact the poorest people in the country. Defunding proven homeless solutions is not only inhumane, but will also increase crime and the number of unhoused people. I’m hoping that campaign promises don’t turn into bad resource allocation decisions. Finally, I’m hoping we will quit chasing symptoms and start changing systems with pragmatic solutions. May it be so.

Also published on Medium.

Well done lad! Thank you!