“The possession of knowledge does not kill the sense of wonder and mystery. There is always more mystery.”

“Mystery creates wonder and wonder is the basis of man’s desire to understand.”

“Don’t become a mere recorder of facts, but try to penetrate the mystery of their origin.”

The best miracles I’ve experienced in my life are the thriving lives of my two grandchildren who weighed in at less than two pounds at birth, spent their next 105 days in the NICU, and are now bright, beautiful, beaming teens. I do feel somehow blessed by these miracle children even though science played a major role in their survival and growth. Contrary to the scarcity of miracles in my life, I encounter abundant mysteries every day.

It seems to me, however, that miracles play a much larger role in the lives of people in different regions and religions around the world. Their foundations of faith are based in the belief in miracles of one sort or another.

To clarify, a miracle is a surprising event that is not explicable by scientific laws and is therefore considered to be the work of a divine agency.

A mystery, on the other hand, is something not understood or beyond understanding – an enigma.

Throughout history, humans have grappled with ineffable “miracles”, seeking to understand the universe and our place within it.

This pursuit has given rise to a multitude of religions, each with its own set of beliefs and practices. Indeed, a fundamental distinction can be drawn between religions that ground their faith in miracles and those that emphasize mysteries. This post will explore the differences between miracles and mysteries, contrasting the miraculous foundations of Islam, Christianity, and Judaism with the mystical essence of Taoism, Hinduism, and Buddhism. I will then discuss how our views and understandings of mysteries and miracles play out in our daily lives and loves.

Miracles serve as tangible evidence of divine power and often form the cornerstone of religions that emphasize a personal God who actively intervenes in the world. These religions often have a historical narrative centered around prophetic figures who perform miracles to authenticate their divine mandate. For example:

- Christianity is founded on the miracle of Jesus Christ’s virgin birth, his miracles of healing and exorcism, and ultimately his resurrection from the dead. About 2.4 billion people identify as Christians.

- Islam reveres the Quran as a miraculous revelation delivered to the Prophet Muhammad. The Prophet’s Night Journey and ascension to heaven are also considered pivotal miracles. About 2.0 billion people identify as Muslims.

- Judaism traces its origins to the miraculous exodus from Egypt, the parting of the Red Sea, and the revelation of the Torah to Moses on Mount Sinai. About 16 million people identify as Jews

In contrast, mysteries invite contemplation and inner transformation. They are not meant to be fully grasped by the rational mind but rather experienced through intuition, meditation, and spiritual practice. Religions focused on mysteries often emphasize the interconnectedness of all things and the pursuit of enlightenment or liberation from suffering. For example:

- Hinduism encompasses a vast array of beliefs and practices, but at its core is the concept of Brahman, the ultimate reality. Through practices like yoga and meditation, individuals seek to realize their unity with Brahman – the supreme spirit and divine consciousness that is present throughout the universe. It is considered to be eternal, unchanging, and the spiritual core of the universe. Hindus believe that all living beings carry a part of Brahman within them, known as the atman. About 1.2 billion people identify as

- Buddhism focuses on the Four Noble Truths, which articulate the nature of suffering and the path to its cessation. Through practices like mindfulness and meditation, individuals can attain enlightenment and liberation from the cycle of rebirth. About 500 million people identify as Buddhists.

- Taoism centers on the Tao, an ineffable principle that underlies the universe. It emphasizes living in harmony with the Tao through simplicity, spontaneity, and naturalness. About 20 million people identify as Taoists.

(Note: In case you haven’t yet done the addition, over 75% of the people in the world identify with one of these six religions – more on that later.)

While miracles and mysteries represent distinct approaches to the sacred, they are not mutually exclusive.

Many religions incorporate elements of both. For instance, while Christianity emphasizes miracles, it also embraces mystical traditions like contemplative prayer. Similarly, some schools of Buddhism acknowledge the occurrence of miracles, but they are not considered central to the path of enlightenment.

Personally, I’m fascinated by the mysteries of life and confused by the need for miracles. When I think of the origins of the universe 14 billion years ago and the evolution of one and two celled organisms into thinking and relating species over that period of time and space, I am filled with wonder and awe. I guess I could say the fact that I’m even alive seems miraculous, but I’m more inspired by the mysteriousness of life.

The question I’ve been thinking about is: At what point does the mystery-miracle continuum become a mobius loop?

It seems to me that it is a human strength to view the world with awe and wonder, appreciating the abundant mysteries that are constantly unfolding around us (for example, a beautiful sunset or snowstorm). At what point, however, does that strength turn into a weakness by reducing the spiritual mystery to a religious miracle, transforming it into a material event, and then losing track of its real meaning. What is lost by confining this expansive notion to a reductive event? What do we miss when we try to explain the immaterial with a material example?

I believe Wittgenstein had it right – language has its limits. Science sometimes can’t explain experience.

The belief in miracles make life simpler, whereas understanding mysteries make life more complex.

Wittgenstein’s theory of language posits that language is fundamentally limited in its capacity to represent the world. The ineffable lies beyond the limits of language. Anything that transcends factual representation falls outside the scope of language, including mystical experiences, deep emotions, and spiritual insights. When we try to put the ineffable into words, we end up falling way short of expressing the meaning we want to portray. While language cannot capture the ineffable, it can be experienced directly. Wittgenstein saw mystical experiences as a prime example of the ineffable.

In the December 6 issue of Modern Love in the New York Times, a mother shares her ineffable experience of communicating with her son after he unexpectedly died in his sleep when he was 12 years old. In the article, she shares her experience: “The more I opened myself to new possibilities and ignored the voice of logic, the more I began to hear, see, and feel things I never had before.” She goes on to describe her experience of continuing to communicate with her son after his physical death on earth. I highly recommend the article.

The concept of an afterlife, a state of existence or consciousness that continues after physical death, is a central tenet in many religions worldwide. However, the specific beliefs about the nature of this afterlife vary significantly. Some religions emphasize an enduring connection between the living and the departed, while others focus on the miraculous aspects of resurrection and life after death. For example,

- In Judaism, there is a strong belief in carrying on the legacy of loved ones – remembering who they were. Central to these views is the belief in the sanctity of life and the enduring connection between the living and the departed.

- In Indigenous and Eastern religions, adherents believe there is a continuous connection between the living and deceased and an active participation of ancestors in the lives of descendants.

- In Shintoism, followers honor and communicate with ancestors in an ongoing relationship.

- In Hinduism, people believe in reincarnation and lingering spirits carrying karma and consciousness between lives.

- In Christianity and Islam, most followers believe in resurrection and eternal afterlife – a transformation of existence beyond the physical realm.

- In Judaism, there are diverse views from bodily resurrection to simply living a meaningful life in the world while we are here. Divine judgment is also a commonly held belief among people practicing different forms of Judaism.

Where we stand on the continuum of mysteries to miracles influences how we view religion, death, politics, how the world works in general.

Even our politics are impacted by our stance on miracles and mysteries. Donald Trump ran on promises of performing magic and achieving miracles. 77 million Americans bought the pitch even though his promises were based on flimsy or faulty foundations. Many voters actually believed he was an instrument of Divine intervention. Not surprisingly, I have no belief that his promises to magically improve the economy with tariffs and mass deportation or to miraculously end the Ukraine invasion, Mideast wars, or the emerging China threats will come to fruition. May I be wrong. It’s a mystery to me that so many people believed these claims.

In fairness (not that I am inclined to be fair and balanced with any comments about Trump), preachers, pundits, and politicians have engaged in magical thinking throughout history. For recent examples, think about the promises and assurances that were made at the beginning points of 12 years in Vietnam, 6 years in Iraq, and 20 years in Afghanistan. It’s no mystery that we ended up with a communist regime in Vietnam, greater Iranian influence in Iraq, and the Taliban in Afghanistan. Clearly, there were no miracles. But let’s not go any further down this path and return to the abundance of mysteries in our lives.

The quotes at the beginning of this post capture a good share of my beliefs about the mysterious. First, Anais Nin suggests that knowledge doesn’t need to kill wonder and mystery, AND there is always more mystery. To me, science brings spirituality to life. I have written extensively about that possibility in previous posts. I firmly that believe mysteries abound if we are willing to pay attention.

Neil Armstrong, with his perspective from space, shared how his experience gave him a sense of wonder and created an even greater desire to understand.

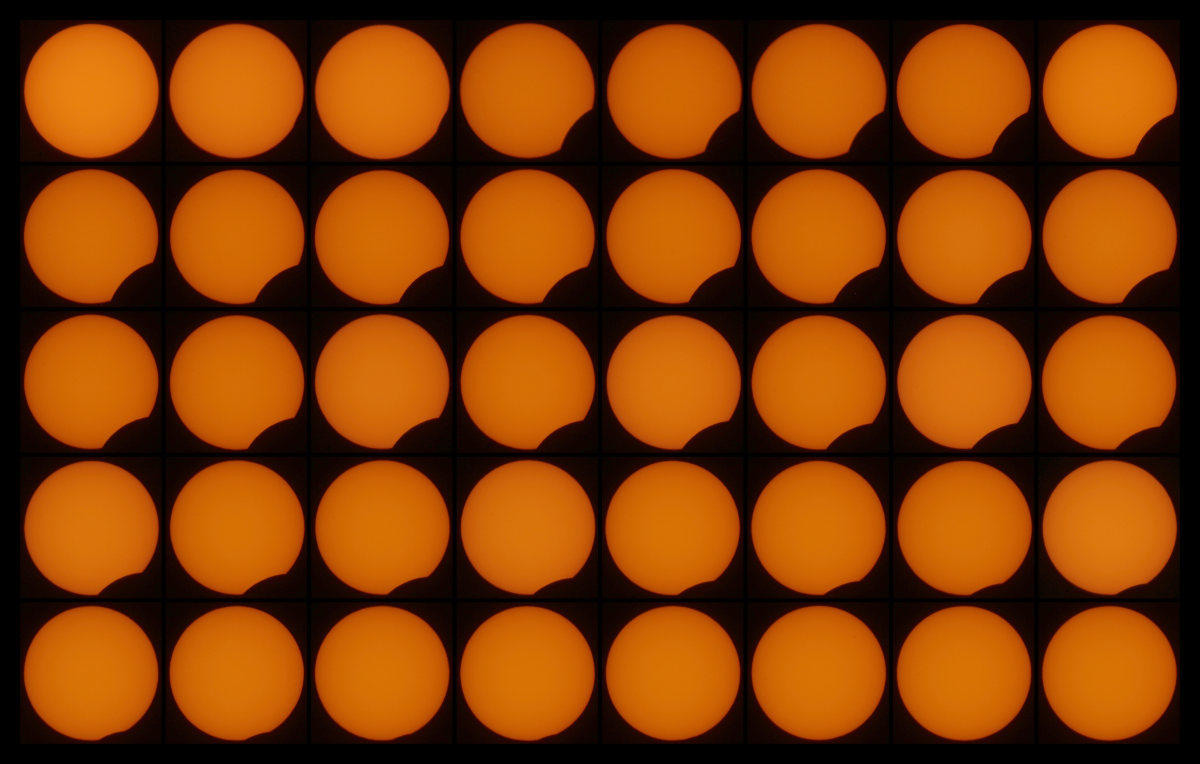

His image of the earth from outer space has inspired environmentalists all over the world. When I think of the origin of the Universe and our beautiful planet, I am filled with awe and wonder as I am when I go for walks through the woods. Nature is full of wonder and fuels our need to understand more deeply its inner workings and scientific underpinnings.

And, surprisingly, the originator of conditioned responses (Pavlov), implores us not to limit our knowledge to a recitation of facts, but to penetrate the mystery of their origins. While I view S-R conditioning (Pavlov’s dog) as a science that fails to appreciate the possibilities of human processing, it still provided a scientific basis for describing the actions (non-thinking responses) of humans and animals to various stimuli. Thus, I was pleasantly surprised to find the quote from Pavlov encouraging us to search for diligently for the mysteries of our origins. AND, we need to be more conscious of how we are constantly conditioned by social media to click to every ping.

In conclusion, you may want to ask yourself where you are on the mystery or miracle spectrum. Where do you draw the line between what feels mysterious to you and what feels miraculous? For me, when I was reading a book on Fearless Dying: Buddhist Wisdom on the Art of Dying, I experienced my skepticism kick in when many of the ideas seemed to sound more like miracles than mysteries. As a strong supporter of Buddhist philosophy, however, it was helpful for me to read the book through the lens of mystery or miracle. Hopefully, you will find the construct helpful as well – not only for discriminating what seems real to you, but also to communicate more clearly your beliefs . . . . . if you are so inclined.

Let me close with a brain-teaser. It seems to me that this mysterious or miraculous idea resembles what Barth and Bonhoeffer implied when they discussed the need for “religionless” religions. My understanding of this paradox influences my belief that religious identity with a dogmatic ideology can distract us from the deeper meaning of faith. If you care to pursue this idea any further, see the movie Bonhoeffer.

In any event, I’m hoping we can let go of some of our beliefs in magic and miracles and expand our search for meaning in mystery. I’m hoping we don’t let scientific reductionism limit our spiritual expansionism. I’m also hoping that we don’t let our ideological identity distract us from inspirational inquiry. Finally, I’m hoping we continue to experience the awe and wonder of our mysterious universe. May it be so.

Also published on Medium.

Well done Ricky-thank you!