“Optimism is the faith that leads to achievement. Nothing can be done without hope and confidence.”

“Pessimism is a luxury that a Jew can never allow himself.”

Optimists believe that desired results will occur no matter what the facts may portend. Pessimists believe that bad results will occur no what the facts may indicate. Possibilists believe that desired results can happen given the right conditions and the right amount of work.

In 1982, I co-founded Possibilities, Inc. because we believed that we could help organizations achieve great results if they were able to establish the right conditions and set the right standards for success.

We started by encouraging leaders to set stretch goals, for example: create an environment that inspires commitment, provide opportunities to develop required capabilities, and align the culture with individual and organizational aspirations. So, upfront, we made sure leaders attended to the 3C‘s of change: Commitment, Capability and Culture.

Once the goals were set, we focused on the values we needed to instill as we achieved those goals, i.e. the “how” was as important as the “what.” Usually those values related to interdependence, Innovation, Integrity, and Inclusiveness—the 4 I’s of intelligent organizations. We emphasized that values and objectives had equal weight.

No objective was worth achieving if it meant sacrificing sacred values.

Finally, we followed a systematic process to achieve our goals and to live by our values. We used a 5D process to guide our work: Design, Diagnose, Develop, Deliver,and Determine. We helped clients design a vision that represented the ideal end state.

We then helped them diagnose where they were in relation to the vision and how big the gap was between where they were and where they wanted to be.

Once we knew the gap we developed people and delivered programs to achieve desired results. Finally, we determined how far we had come and how far we still needed to go using by using multiple metrics to measure progress.

Our 3Cs, 4 I’s, and 5D’s covered all the bases for successful change, but we learned over time those elements were not enough.

We discovered we also needed to carefully calibrate the organizational conditions in which the change would take place. How ready was the organization for change? How fast was the organization willing and able to move? Who would need to be involved? What standards of excellence needed to be set? What did success look like to the various stakeholders? In short, what was possible given the conditions?

I recently read two books that underscore the importance not only of the conditions required for change, but also of the importance of diplomacy, transparency, and truth-telling during change.

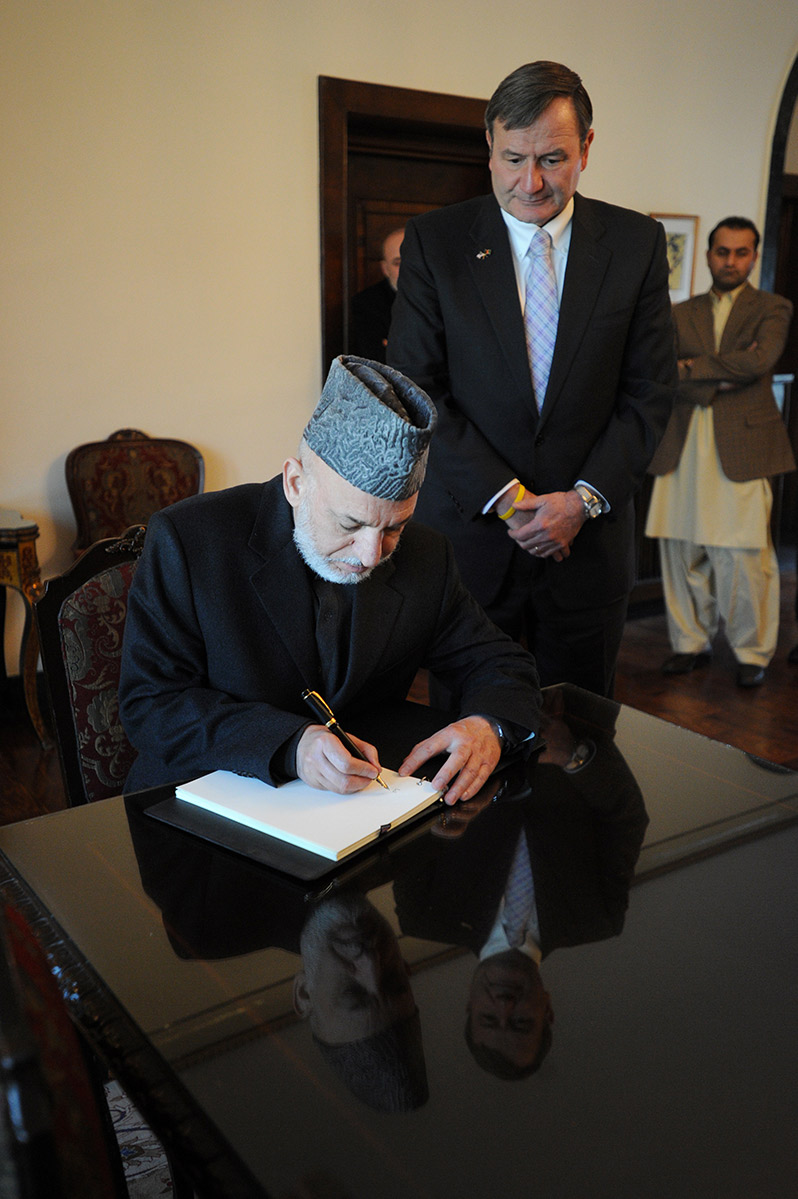

The first book, Our Man by George Packer, is a biography of Richard Holbrooke—a dynamic presence in the tragic conflicts of the past 50 years: Vietnam, Bosnia, and Afghanistan. The second book, Back Channel, is a memoire by William Burns, who also had a heroic career in Foreign Service in Russia and the Middle East.

Both of these books deal with the importance of being a possibilist in the midst of optimists and pessimists.

Richard Holbrooke was the only person in history to be Assistant Secretary of State in two regions: Europe and Asia.

He was a graduate of Brown University and later became a fellow at Princeton. He started his career as a Foreign Service Officer in Vietnam from 1962-1969. His focus on economic development and local political reform were frustrated by the bias for military intervention and regime change. As a result of his experience in Vietnam, he was appointed as a delegate to the Paris Peace talks.

He also wrote pieces for the Pentagon Papers—a top secret report on government decision making in Vietnam.

After Vietnam, Holbrooke served as Ambassador to Germany and to the United Nations. He later served as the Balkans envoy and was the driving force for the Dayton Peace Accords. In addition he was the special advisor on Pakistan and Afghanistan. Throughout his career, he insisted—sometimes aggressively and arrogantly—on understanding the local culture, history and current conditions on the ground before making impulsive, impetuous, or uninformed decisions. He boldly challenged fuzzy thinking and called out the craziness of counter-productive political decisions. Holbrooke worked tirelessly in the trenches in search of diplomatic, sustainable solutions. As a result, his voice was often muzzled or dismissed. The calls for military intervention drowned his pleas for diligent diplomacy.

During practically the same time period, William Burns served under 10 different Secretaries of State and held roles as the Ambassador to Russia, Ambassador to Jordan, and the Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs.

He retired from Foreign Service in 2015 to lead the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He received his BA from LaSalle University and his MA and Ph.D. from Oxford in International Relations. During the course of his career, he played a leading role in eliminating Libya’s illicit weapons and was instrumental in Israel-Palestine cease fire in 2001. He was known for his quiet, heads-down, get-it-done diplomacy. Roger Cohen, in a NYT article, described him as “one of the finest Foreign Service Officers of recent decades, a man of unusual judgment and prescience.” In a memo to the Clinton administration in 1993, Burns wrote:

“Democratic societies that fail to produce the fruits of economic reform quickly, or fail to accommodate pressures for ethnic self-expression, may slide back into other ‘isms,’ including nationalism.”

As the Assistant Secretary of State for Near East Affairs, he strongly counseled the Bush administration against the military invasion of Iraq. Unfortunately, Cheney and Rumsfeld were so determined to unleash the war machine that his appeals were dismissed.

After the invasion, Burns described the grievous missteps that led us into another unnecessary war. He said the “inversion of force and diplomacy” caused the US to become disoriented in a war that was “distinctive for its intensity and indiscipline.”

The push for the use of military force overwhelmed his pleas for diligent diplomacy.

For me, these two books highlight the differences between optimists, pessimists, and possibilists. Clearly, Holbrooke and Burns were possibilist exemplars. They were highly educated, hard-working truth seekers who sought diplomatic solutions in spite of the tidal waves washing over their appeals for more diplomacy and for more sensitivity to the cultures in which we were imposing our values.

They were up against optimists who thought that whatever we wished for would come through as well as pessimists who discounted the value of long-term diplomacy and relationship building.

I wonder if pessimism and optimism are simply mind-sets to avoid doing the hard work of determining what’s possible under certain conditions.

I wonder if pessimists and optimists cling to those mind-sets in order to avoid exercising the discipline of diligent diplomacy because it requires too much patience and restraint.

Being a possibilist means clarifying goals, values, and processes before implementing any change AND analyzing the conditions in which changes are designed to take place.

It means doing the prep work, building relationships, spending time in the culture, and doing the hard work of involving ALL the stakeholders who will be affected by the change.

When my wife and I go on long road trips we often listen to Krista Tippett, the founder of On Being—a radio podcast focused on spirituality. Krista has extraordinary interviewing skills as well as a delightfully captivating voice. At the end of each of her programs, she usually asks her guests,

“What causes you despair and what gives you hope?”

The answers to the question are fascinating in their range and reach. Most of her guests are neither optimists nor pessimists. And they tend to have a couple of traits in common.

One, they have been through too many of life’s challenges to have any illusions that all our plans will work out if we just hope and pray that they will.

Two, they have dug deep inside for the spiritual energy required to work through the most despairing of circumstances.

They are neither naïve, nor cynical.

They have done their work and remain devoted to pursuing the possibilities that life presents to us given the conditions we are facing.

My hope is that more of us will become possibilists. I hope that we will find the faith, hope and confidence, as Helen Keller suggests, to achieve our goals. And I hope, as Golda Meir implores, that none of us allow ourselves the luxury of pessimism. In a time that gives us more doses of despair than reasons for hope, we need to stay focused on achieving what’s possible given the current conditions. May it be so.

Outstanding Ricky! Thank you!