In response to public charges against his high school principle for soliciting sex from a 13 year old, Liam O’Brien, a 16-year-old student at the school, said: “I guess it’s unnerving, but at the same time I almost feel bad because it seems like the Internet creates this wall where people are separated from the reality of their decisions and so they explore things that they normally would never be OK with – that sort of separation can turn somebody who is perfectly normal into something dangerous.” (Boston Globe, 1/7/16)

Some people thought that was a weird thing to say. I thought Liam was being wise beyond his age. Full disclosure: I’m a huge Liam fan. This post will discuss why there is very little wisdom in walls.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines wisdom as the “capacity to judge rightly in matters relating to life and conduct.“ Others have defined wisdom as the right use of knowledge.

Wisdom and knowledge have different meanings. Knowledge has to do with the quantity of data and information you have at your disposal and the ability to process it. Wisdom has more to do with the quality of your words and actions.

The ancient Greeks considered wisdom to be an important virtue. To Socrates and Plato, philosophy was literally the love of wisdom. In The Republic, Plato stated clearly that his utopia would be led by philosopher kings who understood “Good” and possessed the courage to act on their knowledge. Aristotle, in his Metaphysics, defined wisdom as the understanding of causes, i.e. knowing why things are the way they are, which is deeper than simply knowing that things are a certain way.

Wisdom is also important within religions. Jesus emphasized the importance of wisdom; and Paul, in his first epistle to the Corinthians, argued there is both secular and divine wisdom, urging Christians to pursue the latter. Thomas Aquinas considered wisdom to be the father of all virtues. In the Intuit tradition, developing wisdom was one of the primary goals of teaching. An Inuit Elder once said that a person became wise when they could see what needed to be done and do it successfully without being told what to do.

Recent scholars and scientists have expanded and enhanced those earlier definitions. For example, Dr. B. Legesse, a neuropsychiatrist at Harvard Medical School, offers a theoretical definition that takes into account many cultural, religious, and philosophical themes. He defines wisdom as a superior ability to understand the nature and behavior of things, people, or events. He suggests that this deep understanding results in an increased ability to predict behavior or events which then may be used to benefit self or others.

I would add that wisdom is not only related to more accurate predictions, but also to more complete descriptions and more powerful proscriptions.

Thus, wisdom is the application of knowledge to attain a positive goal by receiving instruction in governing oneself. (I would say that Liam’s principal clearly failed on at least two counts: attaining a positive goal and governing himself.)

In short, wise people are better able to describe, predict, and proscribe; more inclined to share accrued benefits beyond their immediate or extended “tribe”; and more able to promote the survival, cohesion, and well-being of the whole.

For me, wisdom is the ability to think multi-dimensionally, to act interdependently, and to feel compassion toward “others.”

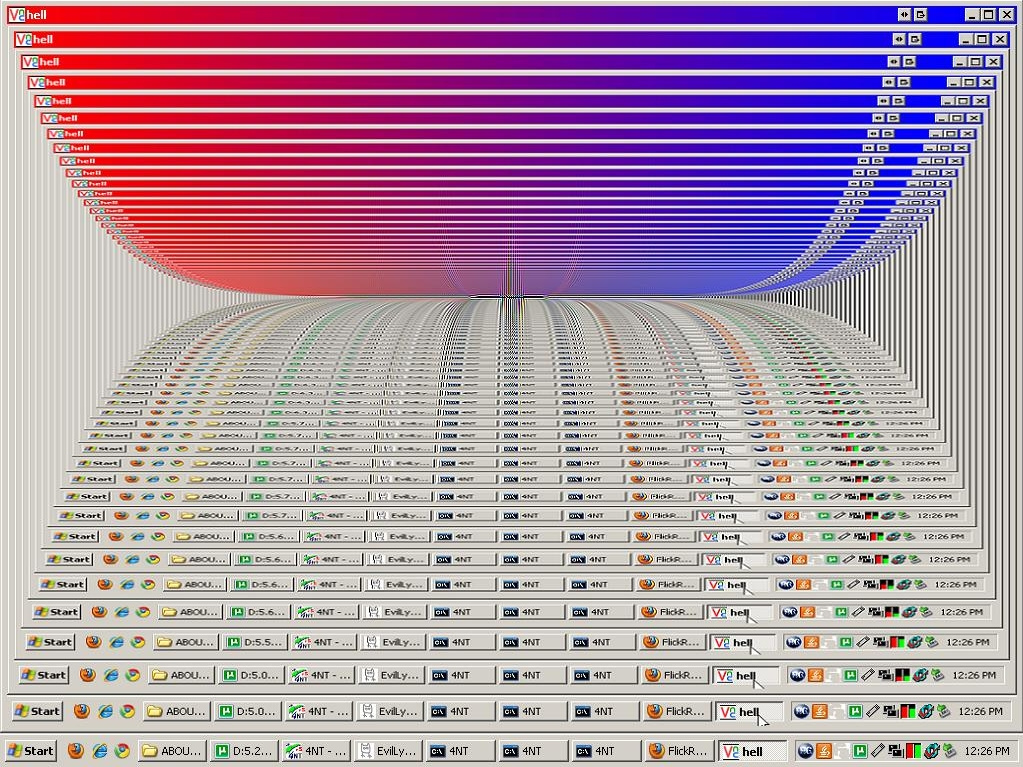

This scale shows the relationship among information, knowledge, and wisdom. You can see that great things are possible at levels 4 and 5, and practically any positive action is impossible at levels 1 and 2:

- 5.0: Wisdom: Right and realistic judgments relating to life and conduct

- 4.0: Creativity: Innovative and implementable ideas based on deep knowledge

- 3.0: Knowledge: Processed and purposed information

- 2.0: Information: Contextualized and conceptualized data

- 1.0: Data: Raw and/or random facts

Currently, many of our educational institutions are focused on data, i.e. memorizing facts in preparation for tests. Many of our business institutions are focused on information, i.e. the analysis of metadata.

I have no idea what governmental institutions (local, state, and federal) are focused on, but it’s sure not innovative solutions or right and realistic interventions. Think Flint, Michigan. And I’m still trying to find institutions that are processing multi-dimensionally for the purpose of establishing more interdependent relationships. Please enlighten me if you have any examples.

Enough about wisdom. Let’s talk about walls.

As a geo-political example, let’s look at the refugee crisis in the world.

Sixty million people are currently displaced from their homes and/or disrupted in their lives.

Thousands of refugees continue to arrive in Europe each day facing huge walls; not only physical barriers — fences, closed borders, and barbed wire — but an even deeper resistance, in the nationalism and xenophobia bubbling up across the Continent. Walls are real and we are bombarded with reckless talk to build bigger ones. As Liam pointed out, even the internet can be a wall by keeping people from face-to-face, authentic interactions.

In a recent New York Times “The Stone” article titled ”What Do We Owe Each Other?” (1/19/16), Aaron Wendland, a research fellow at the University of Tartu, in Estonia, discusses the origin of the walls and what’s required to destroy them. In this article, Wendland discusses the work of Emmanuel Levinas who was a student of Husserl. Having survived a Nazi prison camp in World War II, Levinas’s main concern was to describe the concrete source of ethical relations among human beings. He concluded that the origin of the walls we build is our inability to respond to the wants and needs of others.

Wendland goes on to suggest that

“a handful of recent events—Islamic State attacks in Istanbul, Paris and elsewhere, as well as the mass assault of women in Cologne, Germany, on New Year’s Eve—continue to feed a deep-seated and often irrational fear of the ‘other.’”

And then there is the debate about refugees coming to the United States, where a nationalist sentiment has also emerged, often in the rhetoric of certain presidential candidates.

The point is that doors are being closed to refugees around the world and bigger walls are being built both physically and emotionally. The question is, “Don’t we owe the suffering and disposed something more, if we are to call ourselves human?”

As I’ve discussed in previous posts, over-identification with any particular tribe or ideology is a recipe for disaster. Identification and generalization are bricks in the wall. Fear is the cement.

Levinas argues that the requirements for tearing down these walls are inclusion, hospitality, and basic humanity. His extensive body of work offers valuable lessons about the nature and danger of nationalism as well as the critical importance of welcoming, sharing, and protecting vulnerable human beings. In short we need to quit building stronger walls and start building more welcoming hearts. We need to start feeling more at One with All, and stop clinging to the “same.” We need to open to the “other.”

Levinas implores us to see the “infinity” in human beings – the totality of who they are and quit reducing the full potential of a person to a trait – or the color of their skin. In the “Stone” article, Wendland applauds Levinas for teaching us that “our responsibility for others is the foundation of all human communities, and that the very possibility of living in a meaningful human world is based on our ability to give what we can to others. And since welcoming and sharing are the foundation upon which all communities are formed, no amount of inhospitable nationalism can be consistently defended when confronted with the suffering of other human beings.”

Unfortunately, coming back to Liam and his generation, younger people are not necessarily gravitating to this need for more welcoming, sharing, and hospitality. Richard Weissbourd, a senior lecturer at Harvard’s education school and director of the school’s Making Caring Common project, published the results of a survey of over 10,000 middle and high school students that asked them what mattered most: high individual achievement, happiness, or caring for others. Only 22 percent answered caring for others.

These kids are so driven to “achieve” that many of them who are admitted to top schools come in fried before they hit the pan.

Frank Bruni, a New York Times columnist, describes it this way:

“They enter college as emotional wrecks or slavish adherents to soulless scripts that forbid the exploration of genuine passions.”

Perhaps caring more for others instead of being so driven and self-absorbed could free them from their rigid routines and narcissistic narratives.

For me, it’s a terrible human tragedy that we build walls around us and between us. They keep us closed to fresh, new ideas and positive energy. I know we can’t open every door to everyone, and I appreciate the challenges of inclusion as highlighted by the refugee crisis. I believe, however, there is no wisdom in building thicker, taller, longer, and more impenetrable walls. Yes, there are people who will try to sneak through the cracks and commit heinous acts, but that’s the risk of staying open to possibilities. The alternative is to close ourselves off and refuse to explore the possibilities of a more open world and a more open life.

Hopefully, this new generation has many people like Liam with the wisdom to see beyond walls. Liam got it exactly right—it is separation and otherness that drives people to commit dangerous and destructive acts. Thanks for your wisdom, Liam—I hope it’s contagious. Being born in the first year of this millennium positions you to shift the culture in a more positive direction. May you and your generation develop more wisdom and fewer walls.