March, 1968. I arrive in Saigon during the Tet offensive. I’m scared shitless.

Having grown up in a rural, middle-class, Midwestern, small town, I’m not exactly used to hearing bullets whistling over my head. How in hell did I get into this hell and what am I supposed to be doing here? In short order, I’m introduced to the craziness: The President of the United States lying on national TV about our involvement in Cambodia; young, fresh-faced GIs in battle fatigues laughing as they intentionally splash young, innocent Vietnamese women in long, white dresses walking along the street trying to go about their lives as the bombs drop and their husbands are killed; kids blown up as they hack their way through the jungle not knowing what to fear more—snakes or VC; generals sending 18-year-olds up mountains through withering fire and then ordering them to retreat, measuring progress with body counts; multi-million-dollar jets dropping napalm on a poor country of humble farmers. This makes no sense. There is no trace of sensitivity. I start counting the days before I can return.

March, 1982. I arrive in Washington, DC to witness the unveiling of the Vietnam Memorial. I’m walking with my wife by my side and my eight-year-old daughter on my shoulders. A familiar face emerges from the subway as we make our somber walk to the memorial. It’s my buddy from Saigon whom I haven’t seen since we lived together in DC after returning from the war. We hadn’t planned to meet.

It just happened. He and I had served in military intelligence in Vietnam and in DC. We had walked together in uniform to protest the Vietnam War in the biggest, candlelight march around the Capital. He had spent the last decade doing research on PTSD and advocating for the Memorial we were about to see. We walk together to the Mall where our fellow veterans are congregating. I’m weeping as I see the human devastation from the war, and I’m hoping that this monument will serve to drill some sense and sensitivity into future foreign policy decisions.

On the drive back home, I write this poem:

Everyone knows a name

of a loved one lost there.

The V rises as the death toll grew

And everyone standing there knew

How senseless the killings were.

The names envelop you and grip your guts.

We remember our friends and the humble huts

Where children died.

Amputees look ashen in their crippled state

Few of us were ever driven by hate

Except toward those who lied.

“It’s all over!” “No it ain’t!” they yell –

chilling testimony of their living hell

of anger and confusion.

The babbling, burned-outs give an empty stare

Their moments of peace are exceptionally rare.

They live with their delusion.

Victims are paying tribute to victims here.

Their torment will continue forever they fear

A very lonely place.

Some sit pensively with tears in their eye

Thinking of someone who didn’t need to die

Pain etched in their face.

Beyond the battle, so many scars

Kept buried with drugs and noise-filled bars

It hurts to talk.

People embrace as we’re struck with the wrong

Memories well up that were repressed so long

Then, alone we walk.

Wearing fatigues saved from the war

Their beards and hair noticed no more

Previous protests largely deplored.

Drained, but proud, parents find a name.

Years of sorrow have made them tame.

Their voice largely ignored.

The Vietnam Veterans continue to mingle

Still struggling, still battered, mostly single

The war still haunts their mind.

We are ripped with anguish at the price we paid

This monument screams out the disasters we made

Yes, we left who we were behind.

June, 2016. I’m 71 years old now and the war still haunts me.

And yet, I feel full of gratitude that I’ve been married to an amazing woman for 46 years, that I am deeply connected to my two daughters, that I have been able to lead a fulfilling career, and that I am still able to spout provocative messages. It could have turned out very differently, and I know that my story is not the norm for veterans of war.

But let me get to the point.

This is a very treacherous time in our relatively short history on this planet.

We are now fighting overt wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Lybia, and who knows how many covert wars in countries below the radar. Meanwhile, Russia, China, Iran, Pakistan, and North Korea continue to escalate the tension with threatening acts and language. How many memorials will it take to drive some sense into our human psyches? How many destroyed lives will it take to develop a little more sensitivity to the impact of war on people—whether they are experiencing the horrors on the front lines or reading about the atrocities on the front pages? And now the Republican nominee for President is severely lacking in sense and sensitivity. This is a potentially lethal equation for real nonsense and gross insensitivity.

“Sense,” in the book, means good judgment or prudence, whereas “sensibility” is more associated with emotionality.

While some believe that Austen’s intent was to pit one against the other, others contend that both are important. I’m in the latter camp. We need to exercise better common sense as well as more sensitivity. We are currently not seeing much evidence of either.

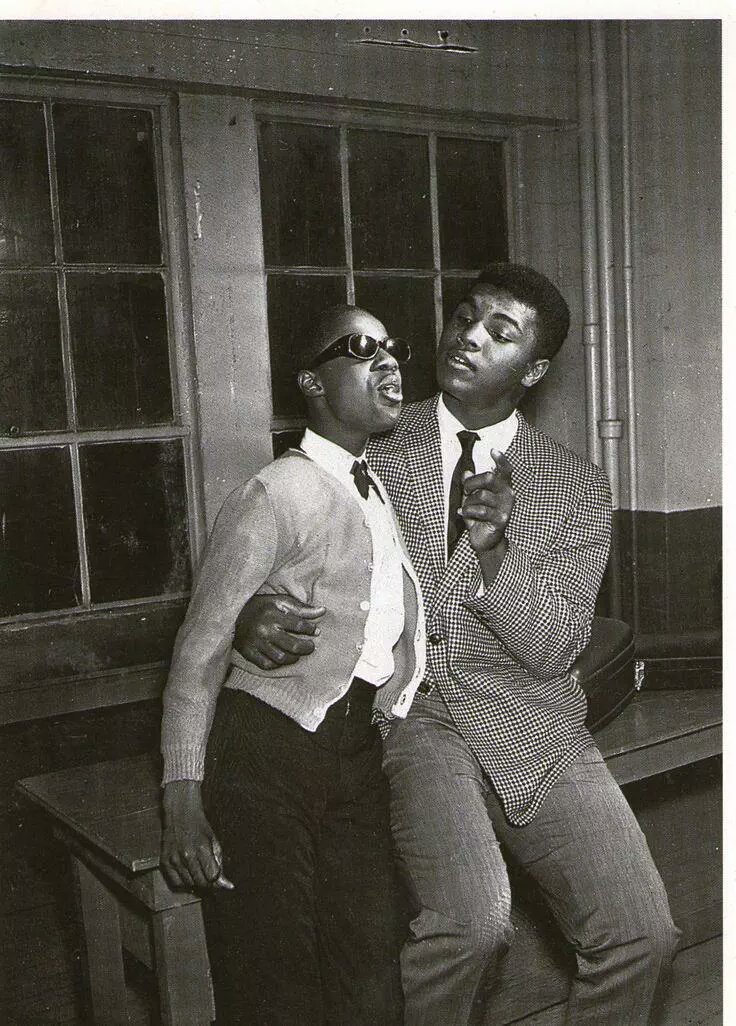

This week a great American hero died. Muhammad Ali was not only one of the most imposing boxers in history, he also danced and sang and wrote poetry with powerful affect. He fought as hard for civil rights as he did for the boxing crown. He even served time in jail because he refused to go to Vietnam and fight in a war he saw as immoral and unnecessary. It seems to me that two of his quotes are particularly relevant to this post:

“On the war in Vietnam, I sing this song

I ain’t got no quarrel with the Vietcong.”

And:

“The best way to make your dreams come true is to wake up.”

Muhammad Ali served as a beacon of hope for many. Perhaps if we listen to his words, we will develop more sense and sensitivity. It’s time to wake up.

http://rickbellingham.com/2016/06/12/sense-and-sensitivity/